In Hayao Miyazaki’s 1997 film Princess Mononoke, we follow the story of mortal men who set out to murder their gods, and take their fate in their own hands. In the film’s mythical setting, the emperor demands that the “Forest Spirit,” the god of life and death, is killed and his head brought to him, because legend has it that the god’s head gives eternal life. Eventually the emperor’s hunters track down the Forest Spirit and manage to run away with his head. The now headless god chases them, trying to get his head back, mindlessly killing everything in his path. One of the emperor’s hunters exclaims mockingly: “Look! He’s a brainless, swollen, life-sucking god of death!” The enchantment is broken: the god may be powerful, but he’s just stupid. The god of life and death is a machine.

“City of Cyborgs” was the theme and title of this year’s exhibition at the STRP Biennial in Eindhoven. The whole festival revolved around the prospect of us being something more than human through our incorporated use of technology. In the festival’s main hall films were played all day long, showing how a modern image of our imagined cyborg future has been cultivated in games and films. The exhibition itself however, situated in another hall, dared to engage with more than just our aestheticised version of the cyborg through a carefully curated selection of installations and artifacts. The exhibition exposed relationships, biases and possibilities, by weaving a web of information, education, criticism, and humour around our prophesied superhuman future and our current attachment to our mechanical and digital companions.

The most subtle yet firm statement about us being hybrids, part machine part human, was made not by a monumental artifact or a cutting-edge invention, but through a short documentary made by Dutch designer Lucas Maassen in collaboration with photographer Mike Roelofs. This video was playing on a screen next to Maassen’s conceptually refined Valerie, my Crystal Sister, a constellation of hanging crystals, whose shape is a magnified reproduction of crystallised human DNA fragments. In the video, Maassen combines footage of his parents talking about their relationship, with interviews of scientists talking about how chemical bonds are formed between molecules. Over the course of the video, the worlds of human relations and chemical reactions entwine, and a captivating counterpoint unfolds about attraction, partners, and being together. Somehow the two worlds stop being a metaphor for each other: it’s impossible to distinguish whether molecules bond like humans, or humans bond like molecules. Bonding and the forging of relationships stop being either human or chemical. They are both. The two worlds have become one.

Another installation at the exhibition titled The Immortal, by Revital Cohen and Tuur van Balen, featured a number of interconnected medical life-support machines. The machines were not connected to a body but among themselves, thus creating a new “body” that is self-efficient and durable. Across the room, two other machines, an interactive humanoid guardian in medieval-like armor made by Freerk Wieringa, and an elaborate robotic puppet by Gustav Hoegen, perform choreographies programmed in them. Like an advanced version of a wind-up mouse, these mechanical bodies repeat again and again a series of movements and actions. In a sense, they imitate life: they pretend to be alive through a reproduction of the movements and para-language that we have associated with life, intelligence and emotion. They enact life and intelligence without actually possessing any of these.

The idea of life as moving surface and choreography that can be reproduced artificially is present in almost all the works featured in the exhibition. For example, in Davide Quayola and Memo Akten’s film Forms, data collected from the movement of athletes is used to create elaborate and fluid computer-generated animations. The athlete’s moving/working body is turned into an abstraction, a series of figures and numbers, which is then used to construct another body. However, this new body is hollow, a hologram of the original body, an empty body. A bit like like Hundini vanishing from a glass pool full of water, the body disappears, leaving only bubbles, traces of its presence; these traces provide the data for the visualisations we see in the film. Thus the film’s beautifully organic animation is in fact always a step behind the body, it picks up what the body leaves behind as it moves, it’s not a body (nobody) but an empty shell of it, a choreographic abstraction.

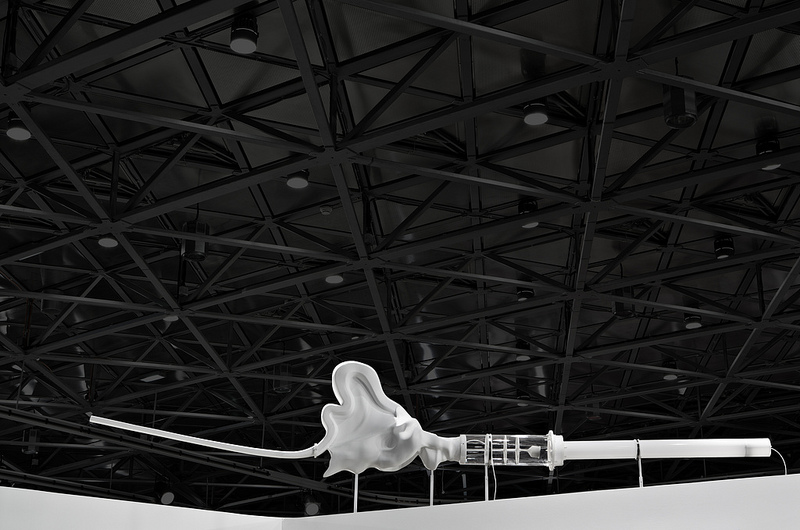

In a similar way Marguerite Humeau’s Back, Here, Below, Formidable is another attempt to reproduce a body out of data. She collected data about certain prehistoric animals from fossils and through interviews with scientists, and then used it to recreate the voices of those extinct animals. Her sculptures are tubular constructions imitating the throat of these prehistoric beasts, through which air is then mechanically pumped to produce sound. While Humeau’s aim is to bring back to life those long-lost voices, the result is hollow and comical, another reminder that a voice, like an athlete’s body, cannot be reproduced, only imitated, and usually this imitation is superficial and in a way empty.

What the work of Humeau and the other artists in this exhibition comments upon is the idea that a living body is merely a sum of its parts. This idea of course is not new. It dates back to Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, where the “monster,” this Victorian android, is stitched together from salvaged body parts and then magically infused with life through a mysterious process of galvanism. It seemed logical that if you put all the parts of a human body together and make them move, a human would thus be made. Since Shelley’s time, this idea hasn’t been abandoned at all in our collective imagination, and can still be traced in science fiction stories like Katsuhiro Otomo’s AKIRA or Masamune Shirow’s Ghost in the Shell, all the way through the work of the artists that we see at the STRP exhibition.

However, it would seem that living creatures are not simply modular machines, and the universe is not a pumping clockwork. The body of interconnected medical machines by Cohen and van Balen described above -that sterilised hi-tech modular body detached from the world and intended to live forever- is in a sense an ironic comment on our desire for immortality. This machine-as-body could be indeed an immortal body, one that could go on functioning forever, only as long as there are servants to repair it, to provide it with electricity, lubricants, filters, fluids, air… However, when its servants stop taking care of it it will simply degrade and eventually stop working. In that sense this Immortal is an unsettling metaphor of Western civilisation and the First World, of a society obsessed with escaping from its mortality and on a quest to stay forever rich, young and entertained. In its greed, the West takes for granted that the rest of the planet’s human and natural resources are rightfully at its disposal for the achievement of this goal, and only the West can be the vanguard -and even the designer, the master planner- of human evolution, and eventually the ambassador of mankind to the stars.

So here we are, at the point where we seriously contemplate shedding our mortality. We still dream of the same thing that every single generation of humans has been dreaming of before us: to become immortal, to deny death. We even contemplate that we can also avoid birth (as Stelarc has already been wishing), by growing embryos in vitro, coming in the world not through a womb but through a sterilised container. Through the imitation of the properties of eternal things (those things that know nor birth neither death but simply are forever) we’re hoping that we too will become eternal, glorious and blissful. Amelia Jones, an American scholar, points out that, indeed, it’s the fear of death and the frustrating mortality of our own soft, wet, vulnerable bodies that drives our obsession with the cyborg promise. [1] From this point of view the cyborg fantasy becomes yet another version of the myth, another Holy Grail, the head of the Forest Spirit, a mythical state we wish to attain in order to be forever, “like the immortal gods.”

It is thus that our current desire to become cyborgs proves to be problematic. We want to control change, unpredictability and variety for the sake of a stable economy and a life that does not end. We want to design and fabricate the future, contain the world and its potential, to preserve the world as we like it. (The neoliberal and colonialist undertones in these statements are alarming.) But as the exhibition at STRP carefully reminds us, there are no humans in a world of eternal life. In order to live forever we need to stop being what we are now, to become a machine that will never change, a body that is merely the sum of its parts. All the works in the exhibition attempted, each in their own way, to recreate a body, or even somebody, through a stitching up of parts: they portray the living body as a modular machine that can be reproduced through assemblage and by apposition. What we are left with however is a deep sense of melancholia, because even our most advanced robotics and our most intricate conceptual contraptions have failed us; we can reproduce the impression of life, but not its essence. And like Mister Geppetto, who made a puppet because he craved for a son, being alive and being human among all these gadgets, devices and machines makes one feel very lonely indeed. As long as we fabricate devices that imitate the appearance of beings, as a ritual of bringing things to life, these devices will be melancholic and comical at the same time. Melancholic in their futile attempt to reproduce or reify something alive, and comical in their failure to be what we want them to be. A reflection of our own comical failure to become, though our inventions, divine, detached, eternal.

Notes

[1] For those interested, this argument can be found in A.Jones’ Stelarc’s technological “Transcendence”/Stelarc’s Wet Body: The Insistent Return of the Flesh. In the volume Stelarc: The Monograph, published by the MIT Press in 2005, pages 87 to 123.

TEXT: Kiriakos Spirou – IMAGES: STRP